Offshore wind farms in the U.S. have been talked about for years. The pioneering effort that brought the industry this far has not been without casualties. These haunt many an investor to this day. Notwithstanding the history, the promising projects that are underway could not have been possible had the drivers not taken the past failures to be foundations to build on, rather than impediments. The authorities in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and soon to follow New Jersey and New York, should be singled out for this praise.

Now it is the turn of the investment industry community to follow the lead. It is a relatively easy problem to solve if debt is guaranteed by revenue. Items such as the generating equipment and cables, etc. that bring power to the land-based grid fall into this category.

What if debt cannot be guaranteed by a long-term revenue commitment but instead by the promise of potential work? That is what is plaguing the development of one of the major items — the installation vessel.

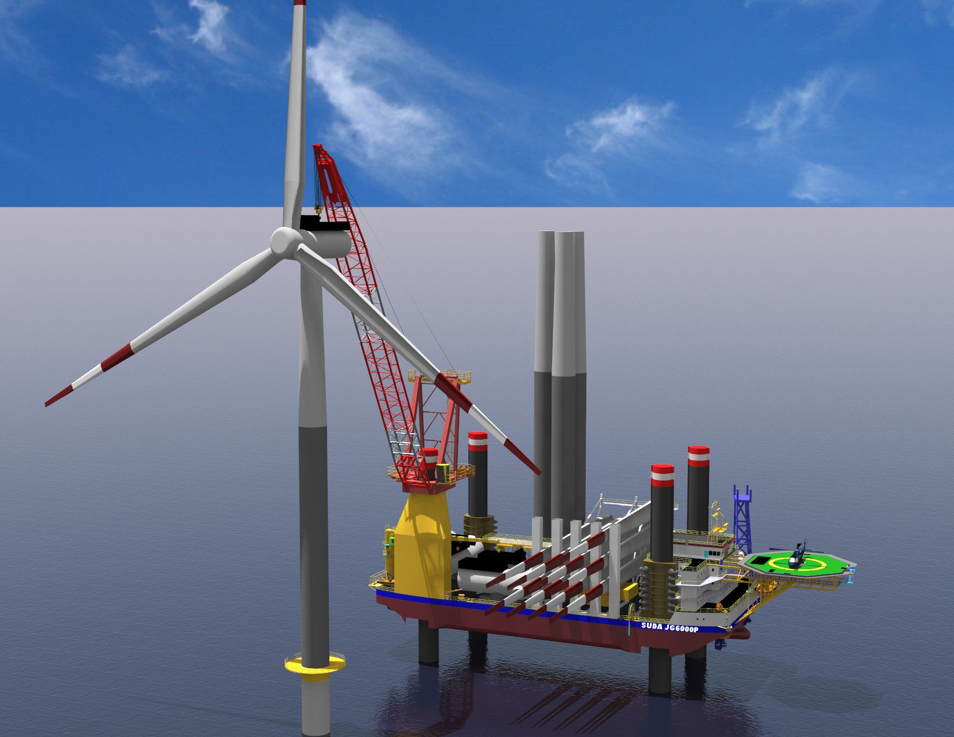

Various studies have yielded impossible requirements such as 10-year firm charter contracts and high day rates. The myth being propounded is that it is extremely costly to build a WTIV in the U.S. (a Jones Act requirement). Some people argue that there is truth to that. Others, like the author, consider it to be a case building effort to justify the Jones Act Waiver to allow using the idle capacity in Europe. Both agree, however, that a waiver is an uphill task.

Creative ideas have been floated to satisfy the immediate needs. One that has been used with qualified success on a pilot project is the feeder vessel concept where liftboats from the Jones Act fleet are used to ferry components to the site. A waiting foreign flag vessel offloads them directly on to the foundation. The problem with this is that the largest available liftboats can only carry about half a turbine. Thus, to carry one 8 MW turbine you need three feeder vessels: one for the tower, one for the nacelle, and one for the blades. Moreover, all the candidate feeder vessels are 3-legged. This increases the preload (by ballast) time; something that is bound to be of concern in this turbo-charged industry.

A twist on the feeder vessel idea is that of transporting the components on a motion-compensated foundation fitted on a barge. The creators of this idea themselves admit this is a short-term solution, as is the other feeder-vessel option. In addition to the obvious limitation of a floating vessel, the modularization as proposed will make the installation costly in terms of both time and money. It is unlikely to win favor from the turbine vendors.

Regardless of the interim solution chosen, it will take more than triple the installation time than for a WTIV with a capacity of four 8-MW turbines.

If there is consensus that the feeder vessel options are interim, costly, and time consuming, why is it that the industry doesn’t go to a permanent solution? There are a few reasons:

Cost of a WTIV

Although the aforementioned studies label this as exorbitantly costly to build in the U.S., those figures can change if we import ideas from the oil industry liftboats. EPCI contractors as well as developers have been shown cost-effective solutions with significantly higher cargo capacities for a given vessel footprint. They have vetted the solutions because the initial reaction was skepticism, given the strong successful standards established in the EU. The result of that scrutiny was the realization of an ideal solution for the U.S. offshore wind farm market, which provides a 33 percent increase in capacity for the same footprint (per a major developer). Added to that is a significantly less expensive vessel than what has been proposed. This has been instrumental in the decision of several developers to publicly support the creation of a Jones Act Compliant installation vessel. Ideas of exporting these concepts to foreign markets such as Europe and the Far East have also been offered, given the promise.

Fear of Obsolescence

This is a serious hurdle to overcome partly due to the uncertainty of the time frame and size of the turbines. If the WTIV technology being proposed now allows for increased upfront capacity, as stated earlier, the promise of a cushion against future higher-sized turbines is built-in. In addition, there are other provisions for dealing with ever-increasing turbine size. Although not willing to divulge full details, the author does note, “In the liftboat world, expandability is our heritage. No liftboat we have designed was for a single purpose only. The WTIV, if sized properly, can have a life in the Oil and Gas sector, also.”

Long Lead Time to Develop and Deploy a WTIV

This is a legitimate concern if action to move is not taken in a matter of months. The current work load in U.S. Gulf Coast shipyards allows for a vessel to be built in 27 months or so. If a WTIV becomes available, it will save an estimated 60 percent in installation time, not to speak of the cost of installation. This luxury can be parlayed to a slightly delayed start.

Uncertainty of Revenue Pipeline

This will not change with time or history. To increase the utilization, the proposed Jones Act Compliant WTIVs are geared to meet the requirement for foundation installation. It could increase the utilization as much as 250 percent. Preliminary studies have shown that commitment of current pipelines is sufficient to secure a substantial portion of the debt while still offering a competitive price to the developers. A willingness by the developers to commit to current and future pipelines, and a willingness by lenders to accept the excellent promise as collateral for debt servicing, is all that stands in the way of launching the project that will guarantee economical and safe installation of turbines and foundations as well as maintenance of the turbines down the road.

The current Jones Act compliant WTIV designs being offered present a risk worth taking. Increased cargo (turbine) capacity results in fewer trips from staging port to site and thus faster installation times. The faster the turbines are installed, the quicker the power can be transmitted from site to shore. There is also the added benefit of the jobs that will be created by this new generation of vessels built in the U.S. The time has never been better to start construction of a Jones Act compliant WTIV.